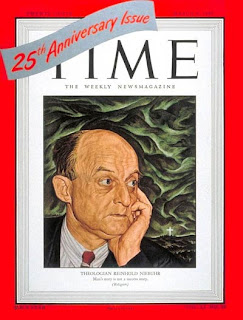

Father Gary Dorrien on the Contempory Relevance of Reinhold Niebuhr

Q. How does your approach to Christian social ethics compare to Niebuhr’s?

A. There have been three major traditions of Christian social ethics over the past century — Social Gospel liberalism, Niebuhrian realism and liberation theology — and Union Seminary has been a major center of all three. Niebuhr absorbed the social justice ethic of the Social Gospel but turned against the idealism and rationalism it shared with the Progressive movement; he believed that the Social Gospel took too little account of conflict and human sinfulness. A generation later, liberation theologians turned against Niebuhrian realism, which they judged to be too much a defense of the American political and religious establishment.

My own work has been influenced by all three of these traditions: by the Social Gospel, by Niebuhr’s powerful blending of theology and political realism, and by the black liberationist, feminist, multicultural and gay rights perspectives that have flowed out of liberation theology and postmodern criticism.

From the beginning of social ethics as a distinct field in the 1880s, social ethicists have debated whether their field needs to be defined by a specific method. Should they burnish their social scientific credentials, or head straight for the burning social issues? Niebuhr is the field’s leading exemplar of directly addressing the social issues of the day without apology. I am on his side of that argument, though I also spend a lot of time explaining that there are other approaches to social ethics.

Q. What insights of Niebuhr’s are most pertinent for the nation’s public life today?

A. His sense that elements of self-interest and pride lurk even in the best of human actions. His recognition that a special synergy of selfishness operates in collectivities like nations. His critique of Americans’ belief in their country’s innocence and exceptionalism — the idea that we are a redeemer nation going abroad never to conquer, only to liberate.

Q. You’ve written two critical books on political neoconservatism. Don’t many neoconservatives claim to be Niebuhrians?

A. In various phases of his public career, Niebuhr was a liberal pacifist, a neo-Marxist revolutionary, a Social Democratic realist, a cold war liberal and, at the end, an opponent of the war in Vietnam. He zigged and zagged enough that all sorts of political types claim to be his heirs. Even the neoconservatives can point to a few things.

But over all, they’re kidding themselves. Niebuhr’s passion for social justice was a constant through all his changes. Politically he identified with the Democratic left. We can only wish that the neocons had absorbed even half of his realism.

The disaster in Iraq is so colossal that people are saying neoconservatism is dead. That’s been said before. Neoconservatives still control a formidable constellation of think tanks, journals and media connections. In John McCain they have a presidential candidate, and they would be welcomed in the administrations of several other Republican candidates. Most importantly, neoconservatism is based on a deep current in American opinion: that the sad lessons of history don’t apply to the U.S. and that we are a nation superior in goodness and power.Q. You have been speaking against the war in Iraq since before it was launched. But what should the U.S. be doing about terrorism, and what is our moral responsibility regarding Iraq?

A. We had a precious moment after 9/11. Not since the end of World War II was there such a possibility to move toward a community of nations. If the U.S. had sent NATO and American forces after Al Qaeda and rebuilt Afghanistan while creating new networks of collective security against terrorism, we could be in a very different world than we are in today. Instead, the U.S. took a course of action that caused an explosion of anti-American hostility throughout the world.

Now we are faced only with bad choices. The cross-fire of sectarian war in Iraq is so complex that it defies concise description. Continuing American occupation will fuel it rather than repress it. Jihadi terrorists are thriving in the chaos.

Whenever an occupier refuses to acknowledge the necessity of pulling out, the aftermath is worse. President Bush warns of chaos if we leave. Indeed, if we simply leave, there will be chaos. Leaving chaos behind is what happens when imperial powers refuse to acknowledge their defeat and the necessity of planning an exit that causes the least possible harm.

In 1947, after years of refusing to accept that imperial rule in India was over, the British cleared out in seven weeks: the country was partitioned, 12 million people were displaced and half a million killed. France and the United States blundered into similar bad endings in Algeria and Vietnam, having refused to face reality for years before rushing for the exit.

Today the U.S. should be planning how to get out of Iraq, how to minimize the bloodshed we’ve made inevitable, how to fund and organize international peacekeepers and humanitarian aid, instead of babbling nonsense about “prevailing” there.

Q. When you take a position like that, do you feel that you are being Niebuhrian or anti-Niebuhrian?

A. Neither. Asking what Niebuhr would think about this or that is a favorite indoor sport. I cannot flat-out call myself a Christian realist in Niebuhr’s sense. His realism makes it too hard to make a Christian claim at odds with the national interest. Yet for me Niebuhr’s thought is always in the mix. And today I believe he represents a road not taken: a prudent foreign policy chastened by a realistic and religiously grounded understanding of the limits of power.

Read it all. What I like best about this interview is that Professor Dorrien does a good job making the case that the neoconservative embrace of Niebuhr displays a profound misunderstanding of what Niebuhr was trying to say.

Comments

This stance really worries me - accepting moral responsibility for terrorist violence. It is not Americans who are suicide bombing civilians in Iraq. Such fanatical killings have been going on for many years, and long before 9/11.